Guest post:

KEVIN MCBRIEN, PhD Candidate in Musicology, University of California, Santa Barbara

—

It is rare to see the words “frivolous” and “Beethoven” appear together in the same sentence. By their very nature, pieces such as the Ninth Symphony and Grosse Fugue seem to exude a profound weightiness and automatically warrant descriptors like “monumental,” “pillar,” or “masterwork.” However, it can be easy to forget that Beethoven repeatedly showcased a lighter, even playful side in his music. The importance of his more serious musical expressions cannot be overstated or ignored, but considering the dashes of frivolity present throughout Beethoven’s output can paint a much richer picture.

The lighter side of Beethoven’s compositional voice is particularly evident in his Third and Fifth Cello Sonatas. The Third (op. 69), which was composed in 1808 and premiered the following year, opens with a broad and stoic sonata-form movement, often considered to be the most “serious” of musical structures. What follows, though, is a startling shift—a mischievous Scherzo set in A minor (the parallel to the Sonata’s home key of A major) and a springy 3/4 meter. This boisterous movement is riddled with rhythmic trickery; random accents pepper both the piano and cello lines, and seem poised to derail the proceedings at any moment. The music here does little overall to reflect the handwritten dedication Beethoven allegedly penned on the Sonata’s now-lost manuscript—Inter lacrimas et luctum (“amid tears and grief”), perhaps a reference to the arrival of French troops outside Vienna in 1809. In fact, the Sonata as a whole rarely mirrors the anxiety of these events and is a delight from start to finish.

Similarly, the Fifth Sonata (op. 102, no. 2) also spotlights a rather surprising moment of lightheartedness. Dedicated to Beethoven’s patroness and friend Maria von Erdödy, many scholars pinpoint this 1815 work as one of the earliest signs of Beethoven’s late period. The music of these final years is characterized by boundary-breaking experiments in form, harmony, and rhythm that would become a crucial jumping-off point for countless composers after Beethoven. Sharp juxtapositions in mood are also common throughout his late-period music, and this Sonata is no exception. After the second movement—a solemn, time-suspending Adagio—the cello segues directly into the finale via an inquisitive D-major scale (disguised as an altered A-major scale). After this is quietly echoed by the piano, the cello reiterates the scale once again, but this time it has suddenly become the subject of a spirited fugue. With a few exceptions, fugal finales were still quite unusual at the time of the Sonata’s premiere, and some audience members were puzzled. One less-than-stellar review from 1824 reads:

“The subject is too cheerful for such a serious execution and for that reason contrasts in too shrill a manner with the two previous movements. How much we would have rather preferred hearing a different movement, a Beethoven finale, instead of this fugue! We wish that Beethoven did not exploit the fugue in such a willful manner, since his great genius is raised well enough above every form.”

As is so often the case, the joke was on the reviewer and this work—along with Beethoven’s other four Cello Sonatas—have since become cornerstones of the cello repertory.

While wonderful on their own, these two examples only scratch the surface. Frivolity is present throughout Beethoven’s output. Take the bubbling Scherzo of the “Eroica” Symphony, the celebratory finale of the “Lebewohl” Sonata, the bucolic folk song arrangements. These moments help lift the veil on a composer who is all-too-frequently thought of as a curmudgeonly artist angrily shaking his fist at the world. Of course, frivolity should not be mistaken for haphazardness—Beethoven’s lighthearted music is just as meticulously thought out and crafted as his serious music. Rather, it is in these lighter moments that Beethoven reminds us that to be human is to experience the gamut of emotions, whether it be quiet despondency or unbridled joy. Frivolity is just another part of the richness of life and for Beethoven, that is serious business.

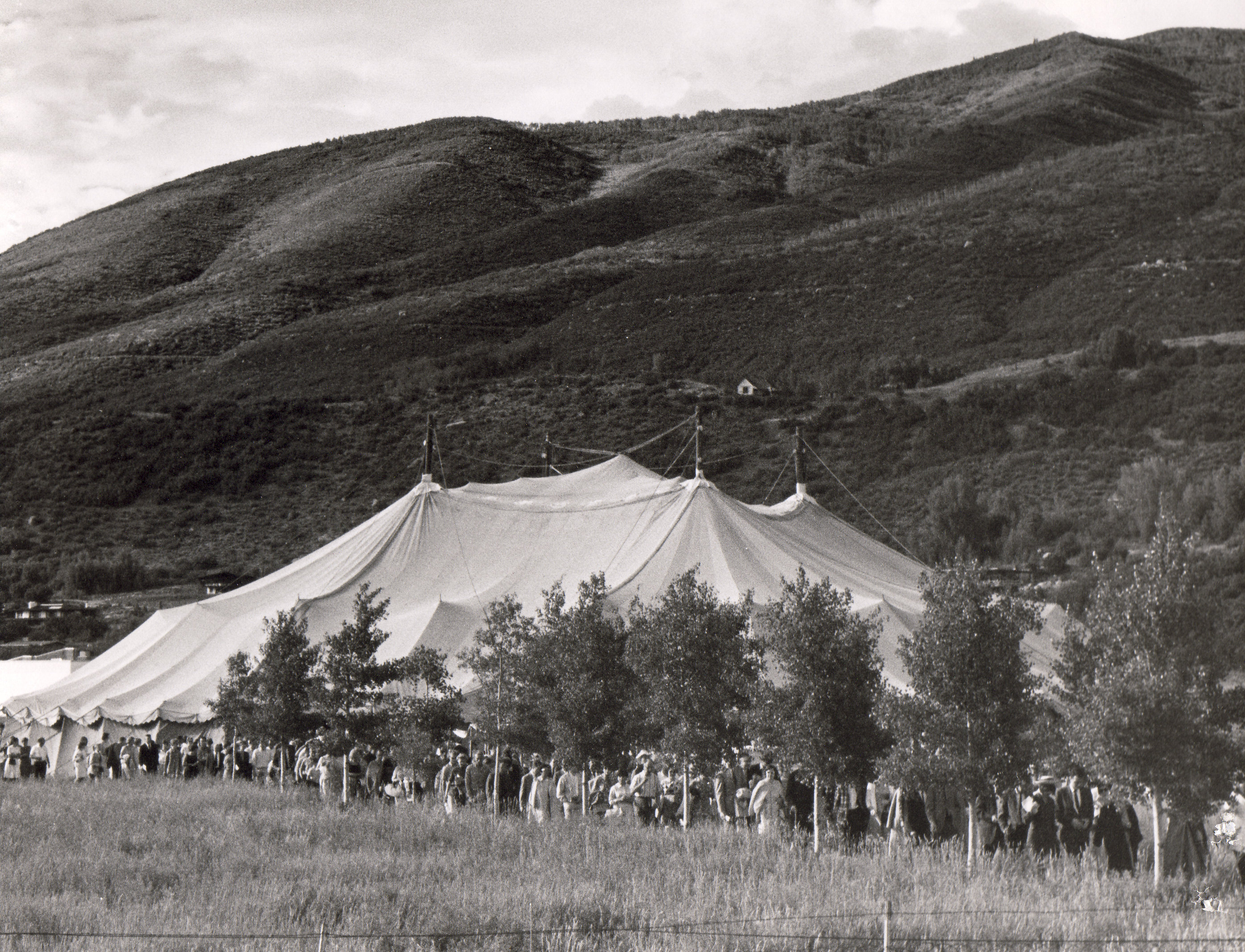

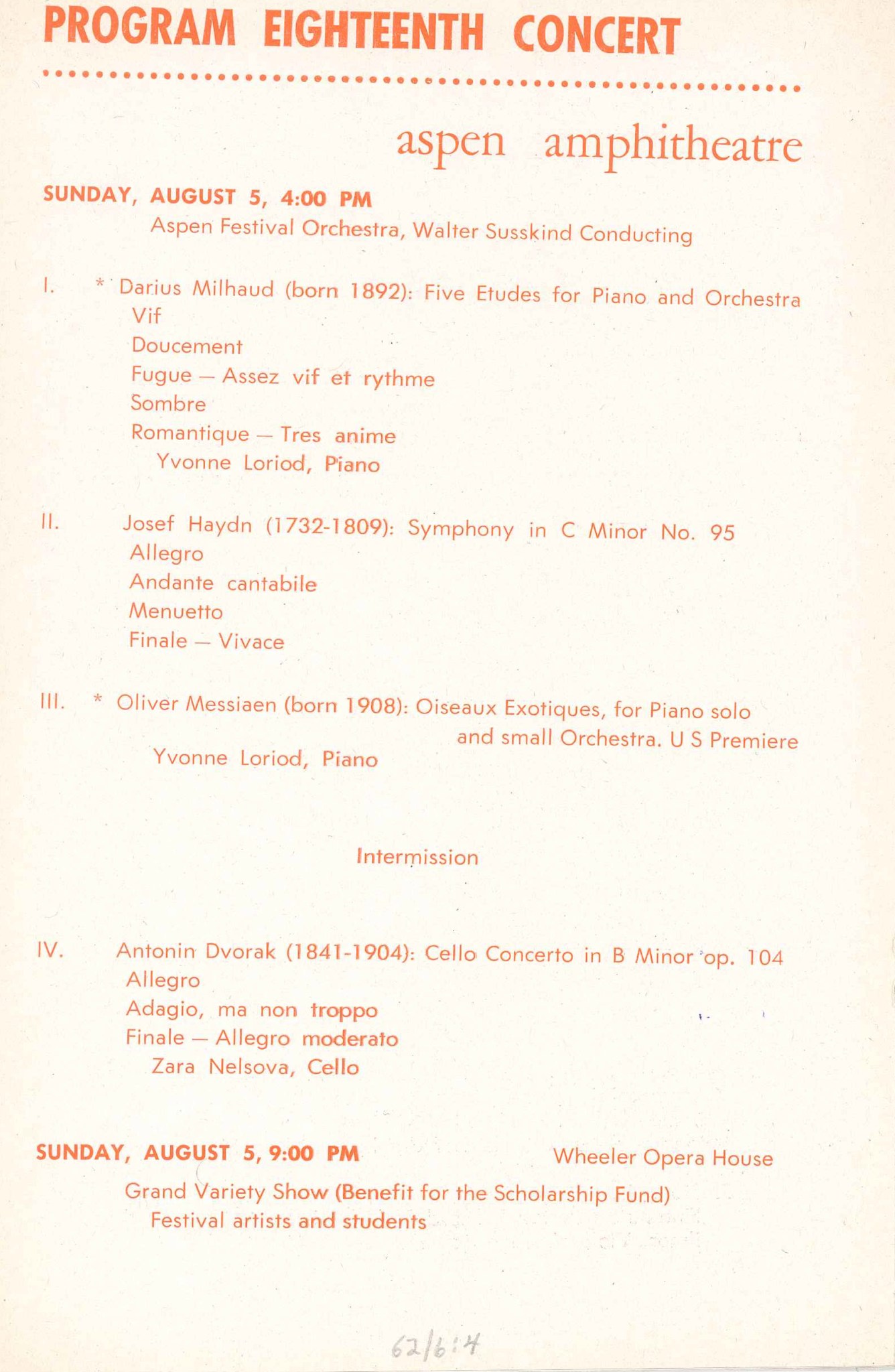

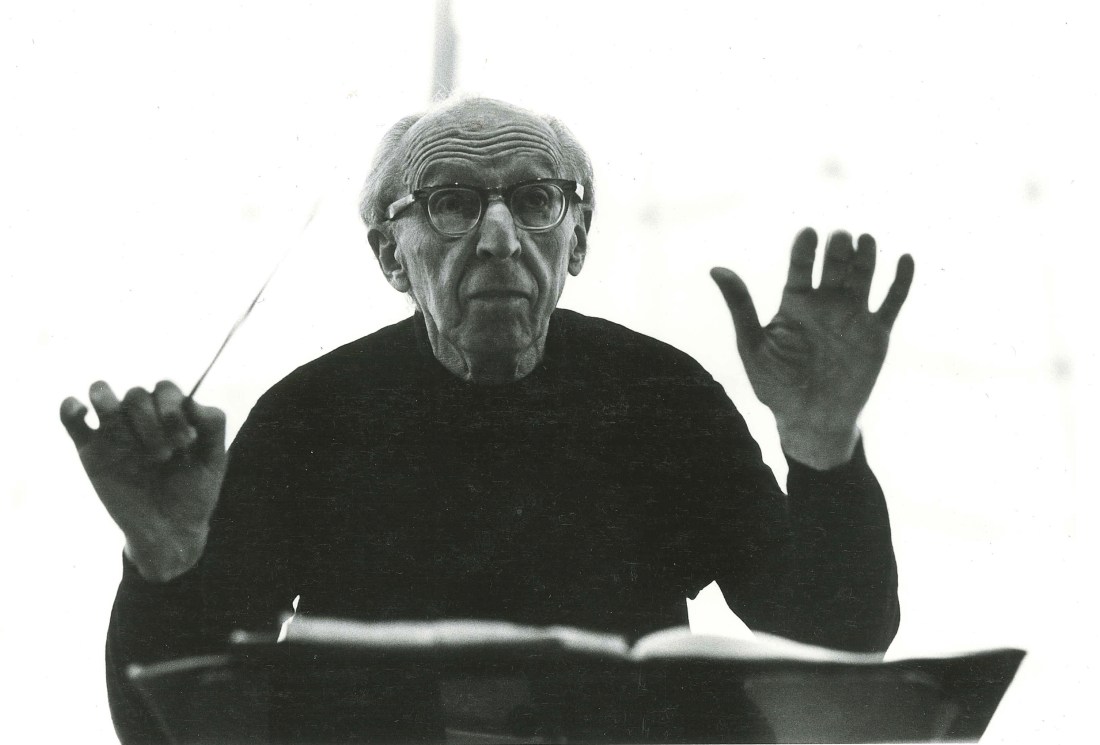

Kevin McBrien is a Southern California-based musicologist, writer, editor, and speaker who has a passion for connecting others with classical music. A PhD candidate in musicology at the University of California, Santa Barbara, his current research explores connections between émigré composers and the Los Angeles Philharmonic in the 1930s & 1940s. Kevin is also an avid program and liner note annotator, and his writings have appeared at the Aspen Music Festival and School, Salida Aspen Concerts, and Music Academy of the West, and in album releases by Chavdar Parashkevov, Natasha Kislenko (Beethoven, Brahms, Mahler: Works for Violin and Piano, 2018), and Sung Chang (forthcoming). Additionally, he has curated a classical music blog since 2017.